1987–2007

Schnee in Samarkand.

Ein Reisebericht aus dreitausend Jahren

Companion volume to

Travelling through the Eye of History

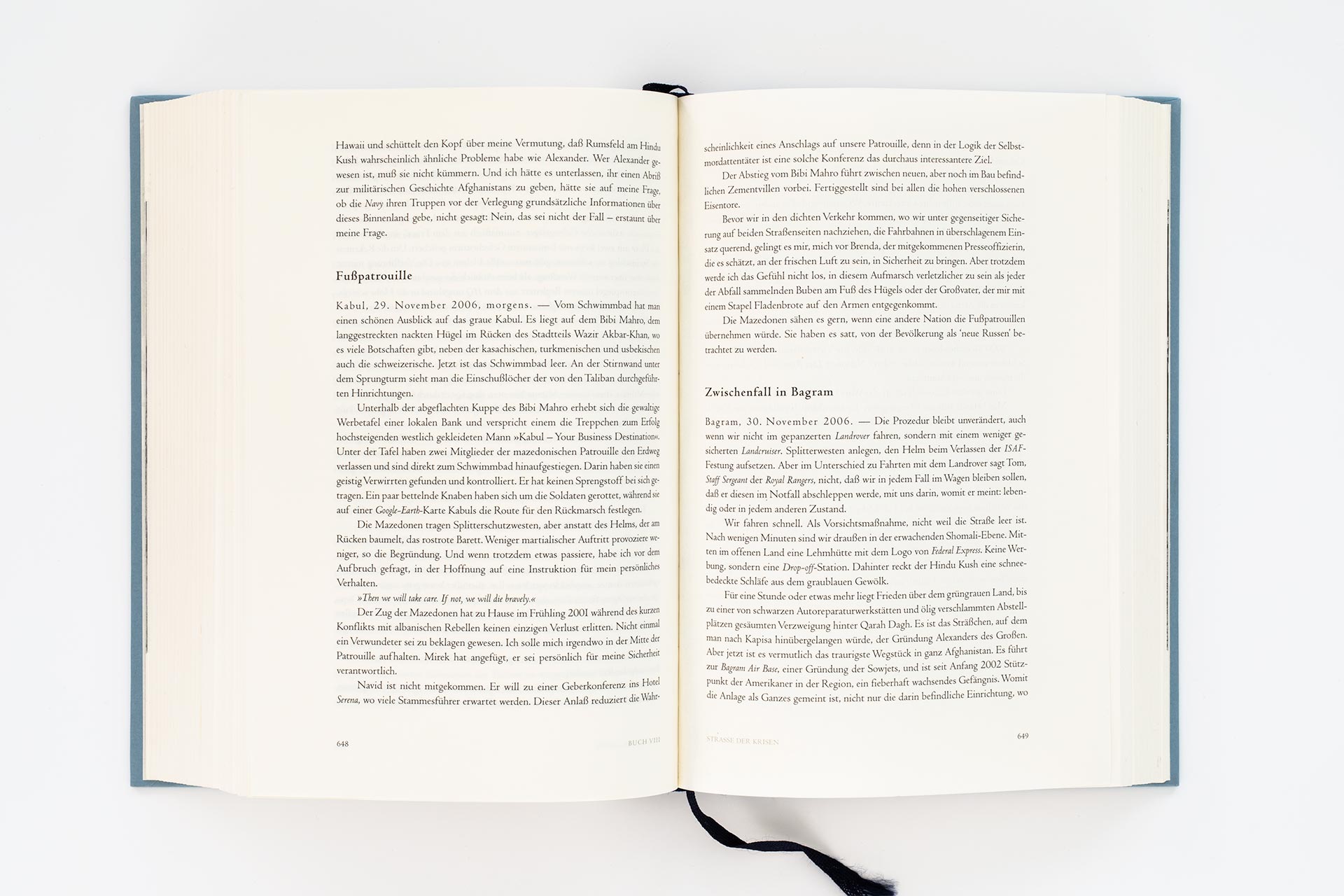

A literary and factual recollection of two decades of perilous travels, this voluminous personal record, supplemented with extensive inquisitive marginalia, deals with 3000 years of history and the material vestiges of the global heartland now occupied by the five Central Asian Republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) and Afghanistan, as well as of the adjoining regions of the Caspian Sea, Iran, Pakistan, Indian Kashmir, China’s autonomous Xinjiang region and Mongolia. Political judgments of our own time are mirrored in the tales of history conveyed.

Thomas Sarbacher reads from the Introduction (Audio file in german)

Read pp 649–653 (PDF. Typeset in Centaur MT Std. Satz: Greiner & Reichel, Köln)

Recounted and interwoven here are myths and stories past and present and the wondrous and troubled affairs of the global heartland – from the earliest times of the diffusion and transmission of knowledge to the formation and collapse of empires, from the Timurid Enlightenment to the perpetual wars in Afghanistan and beyond – all of which draw on a unique range of sources from ancient China, Persia, Greece and Rome, from Byzantium, the Arab Conquests and the Middle Ages, from the Renaissance, the Great Game era and Imperialism, as well as from the non-fiction of our globalizing World.

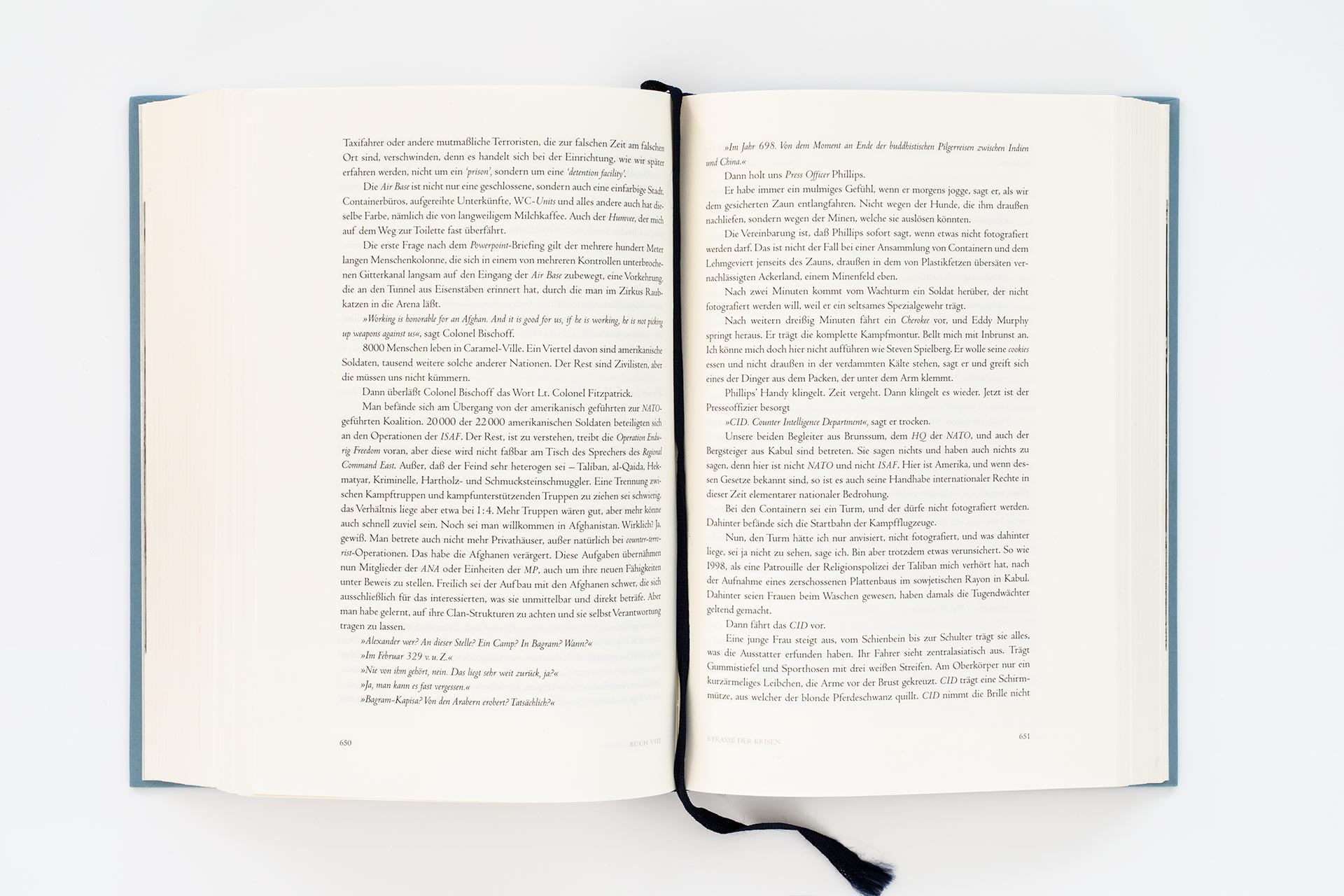

Searching for the Horse Breeders

Kuva, 26 September 2002, afternoon.

…

Securing the Gansu Corridor was a crucial step in the Han’s expansion towards Ferghana. Their passage effectively drove a wedge between the Xiongnu and their allies in the Tibetan foreland. Situated at the end of it, there were the mountain ranges on either side recede, is the newly installed Jiuquan command post, epitomising Chinese control in perpetuity.

On leaving Jiuquan, a bleached plain unfurls all the way to Jiayuguan. Fields of rapeseed coaxed out of it. Expanses of sand. Semi-desert. Then stony desert.

Which under the rainy sky of 30 April 1987 looked grey and flat. So flat and featureless that I wondered how my driver from the cultural authority in Jiayuguan – exuding garlic fumes despite the early hour – would manage not to miss the tomb. But of course this was not the first time he had driven there. He pulled up less than two meters away from an unassuming mound.

The entrance to the tomb was off to one side. Lying on our stomachs, we pushed our legs down into the darkness, our feet feeling for the rungs of the ladder. Finding it, we climbed down to a tunnel and there, hunched over, forged ahead until, after a few meters of nothing, we entered a high dromos and from there, through an archway, the domical vault, in which the previous day’s warmth still lingered and my vanguard’s garlicky exhalations at last yielded to the duller breath of the grey bricks. Painstakingly stacked, these bricks supported a pointed dome sealed off at the top by a square slab. Looming up in the torchlight were all sorts of figural scenes painted onto the ochre-coloured ground of the upright bricks installed in the grey brickwork and framed by broad bands of a colour akin to dried blood.

There were Bactrian camels and peasants leading oxen by their nose-rings or behind a plough pulled by a team of two; hunters on horseback and a fleeing deer struck by an arrow in mid-leap; two women kneeling in front of cooking pots and plucking chickens; a herd of flying horses and next to it a herder brandishing a whip. The figures with ballooning robes and hair, the lithe animal bodies captured in fine, boldly drawn black brushstrokes without impeding their momentum – they were almost upbeat scenes of everyday life. Far removed from the campaigns of Modun, the son of Touman under whom the Xiongnu in the north became a political and military counterweight to the Warring States (475–221 BCE), and who, elevated to the Xiongnu’s Chanyu, reconquered the Ordos from which Meng Tian, the First Emperor’s famous commander of over 300,000 soldiers stationed along the Great Wall, had previously expelled the nomads, it is a nomadic sketchbook painted for a tribal prince who died during the Wei dynasty (220–265), three-quarters of a century before the first Han settlers from beyond the Wei River began their advance up the Gansu Corridor.

(Translated from the German by Bronwen Saunders, March 2024)

The Teahouse of the Immortals

Balkh, 14 October 2002

… Atta is wearing this new uniform with evident pleasure. His polished shoe jiggles against a trouser-leg with a perfect crease.

The general’s eyes are in the shadow of his peaked cap, a shadow that falls over his entire face when, once welcomed by a local rep, he leans forward to speak into the microphone set up between flower arrangements on the small low table. The male population of Balkh, like that of villages elsewhere in the region, has come to see him…

I am standing too far away to understand much, but that the general is not winning hearts and minds easily can be read from the listeners’ faces. The younger men with their blond beards are wondering whether the uncertainties of the future might be weathered better from within Atta’s entourage, rather than that of Dostum, whose position has been weakened. The old men’s faces are hardened by the observation, confirmed again and again, that ascending the throne and being forced off it follow each other like night and day; with the greed of the regent, above all, filling the gap in between. The pomp of the young general does not impress these old men. What is he, if not a fop? Here not as a result of his own deeds. Hustled in, rather, protected by foreign mercenaries. His baby-face, for the moment, still hidden by his own shadow.

Like these old men, Balkh itself – a coronation city for the founders of whole empires – is surprised by this strange visit on a fine morning.

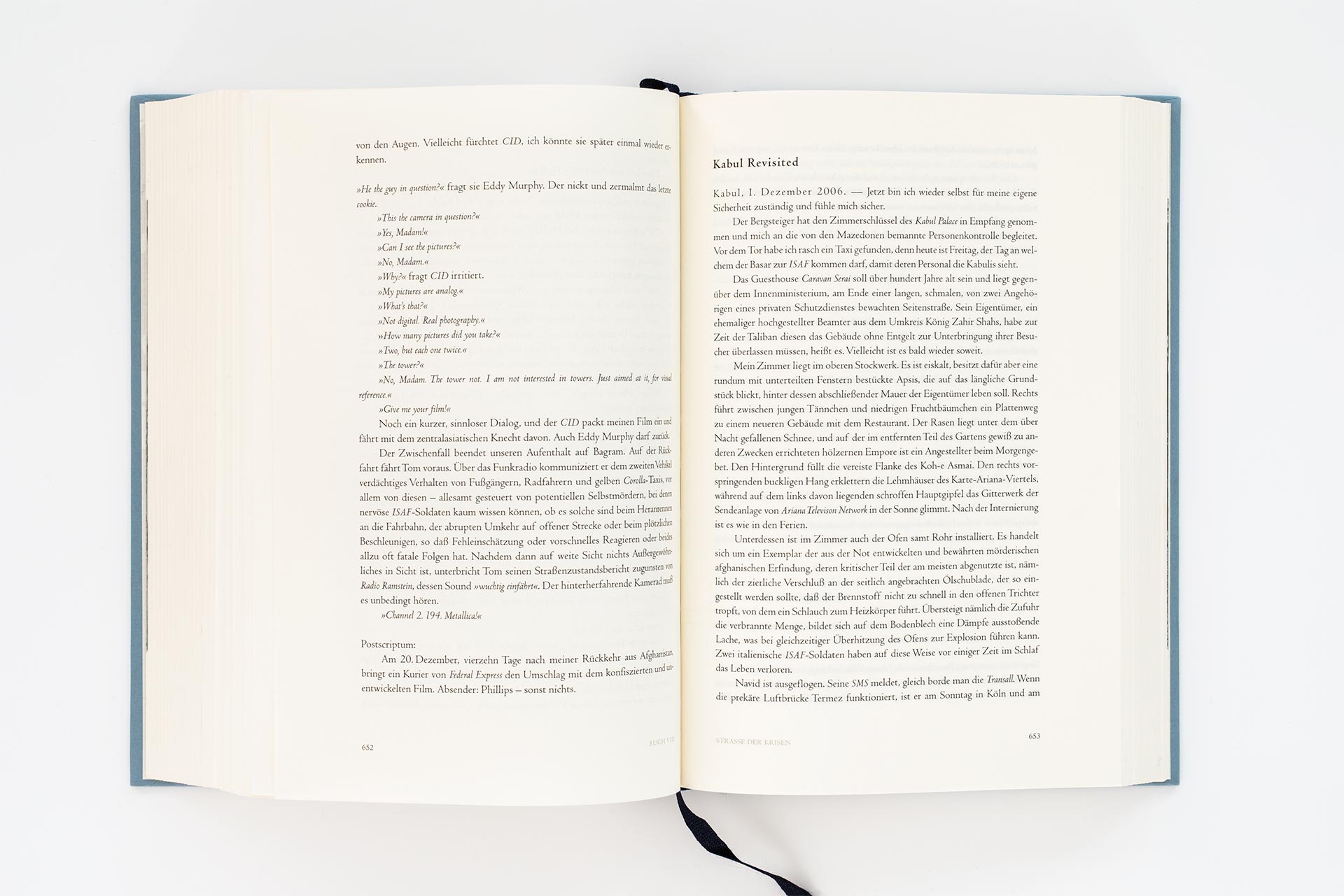

I leave the crowd and the square to go and find a teahouse, a chaikhana. I walk along the curved gravel street until I reach the antique dealer. His shop is barely bigger than a cupboard. The shelves crammed full of antique and fake ceramics – jugs, pots, phials, oil lamps. Am I looking for something? – a teahouse? Not too far. A few steps down the first street off the curve. First, though, several containers with holes cut out of their long sides – cloth merchants. Women crouch in the dust of the street, constantly draping the pleated cloth of the white-as-a-dove and blue burkas. Chinese textiles, with gold threads woven through, flow through henna-painted hands, are lifted into the light that falls through the young poplars.

Soon, I am standing outside the chaikhana. I enter. No-one there. The TV, unplugged. The only movement: the Chinese stand fan continually turning its tilting head from one side to the other, modestly, but also as if it is looking for someone.

I shall wait here for Greg and Marcus. And as I wait, may guests enter the chaikhana: those distant travellers, in the precise order in which, chronologically, they came to Balkh – or left here – on the military roads, caravan routes and pilgrims’ paths of Central Asia. Let their stories connect with that of the town on an imaginary dastarkahn, the table-cloth spread on the ground – the Turki word can also mean ‘feast’ and ‘abundance’ or ‘hospitality’ – on which stand bowls with golden peaches from Samarkand.

(Translated from the German by Donal McLaughlin for the 31st Literaturtage Solothurn festival, 2009)

Account/memoir/reportage

Schnee in Samarkand.

Ein Reisebericht aus dreitausend Jahren

Eichborn-Berlin, Berlin 2008

1000pp

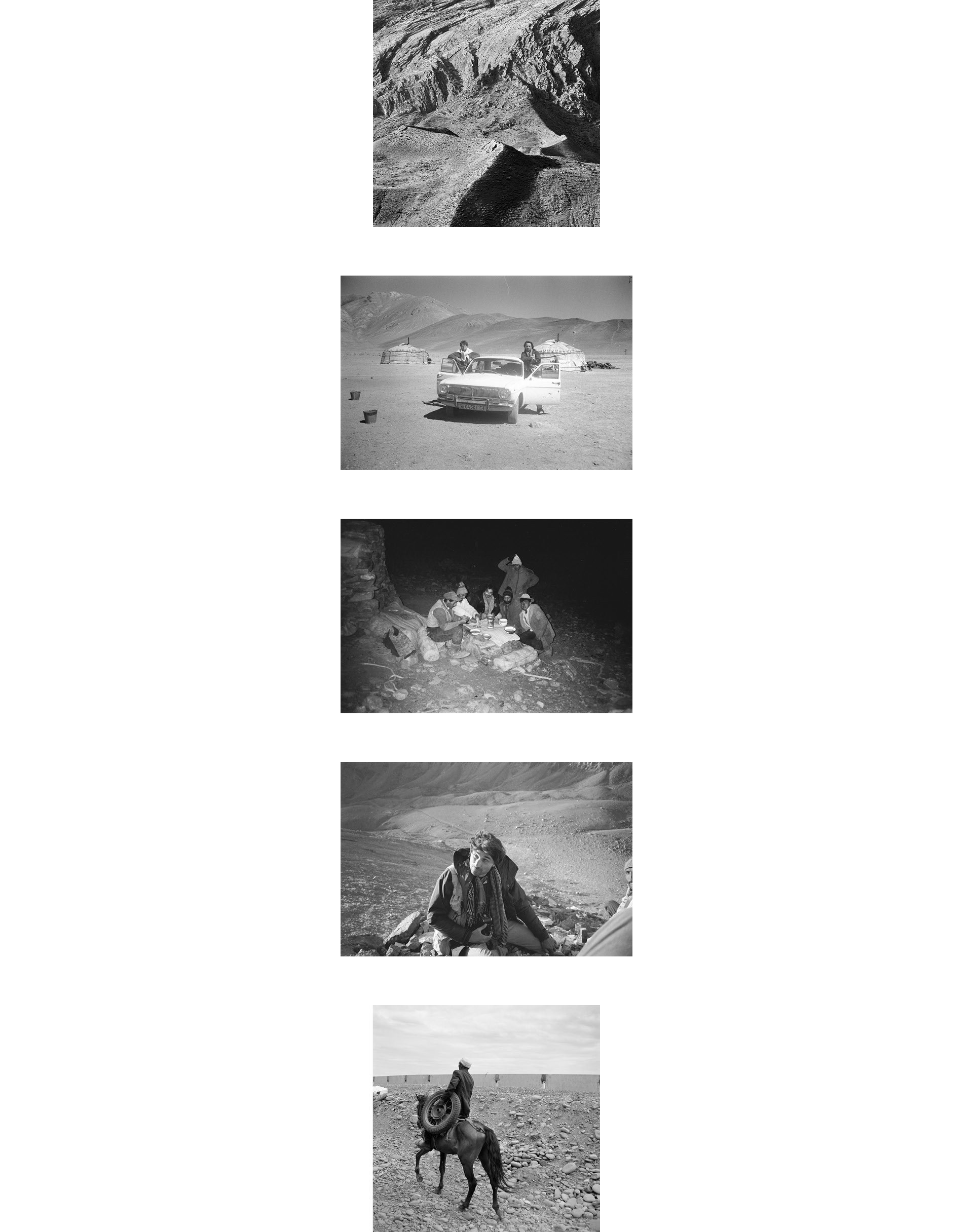

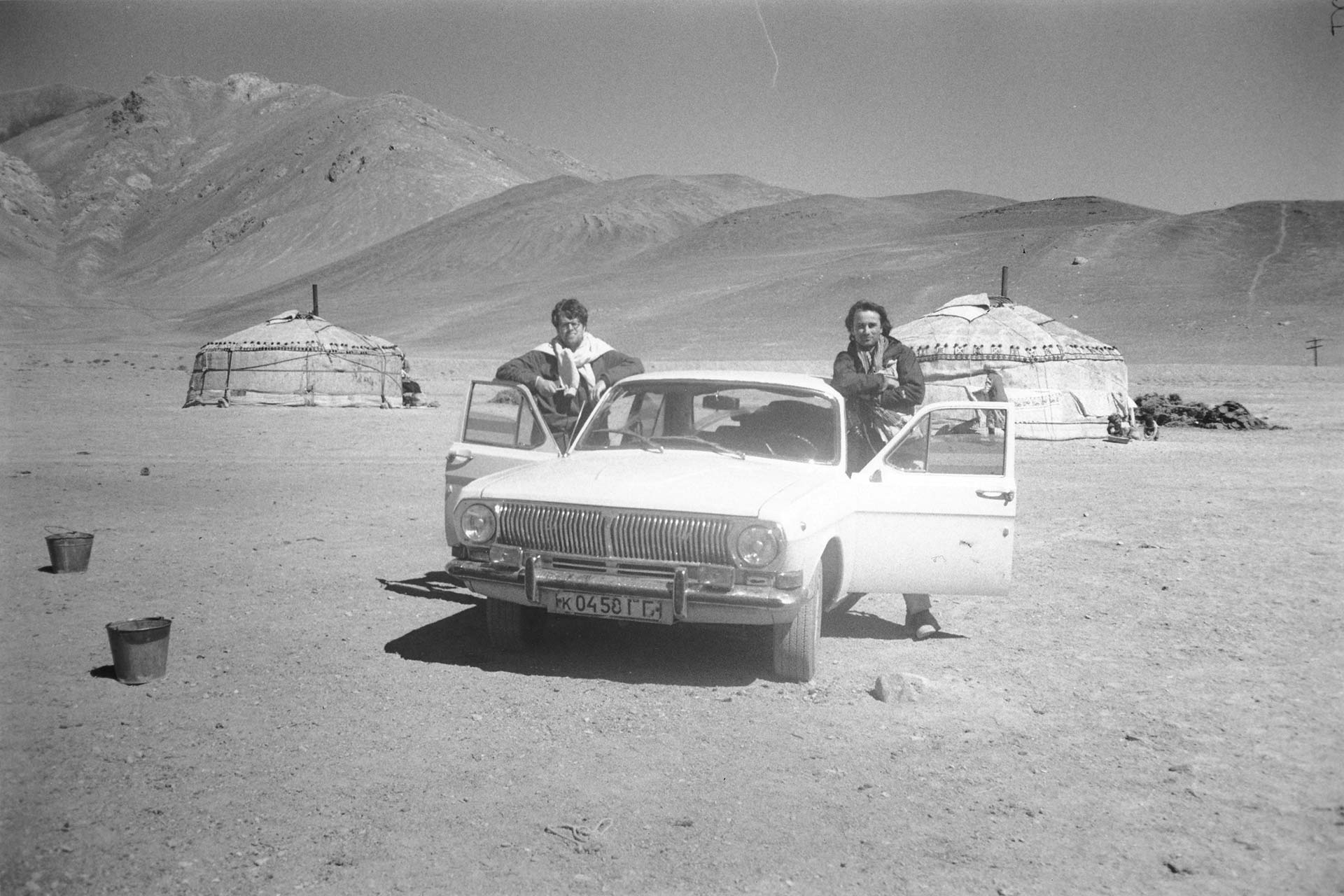

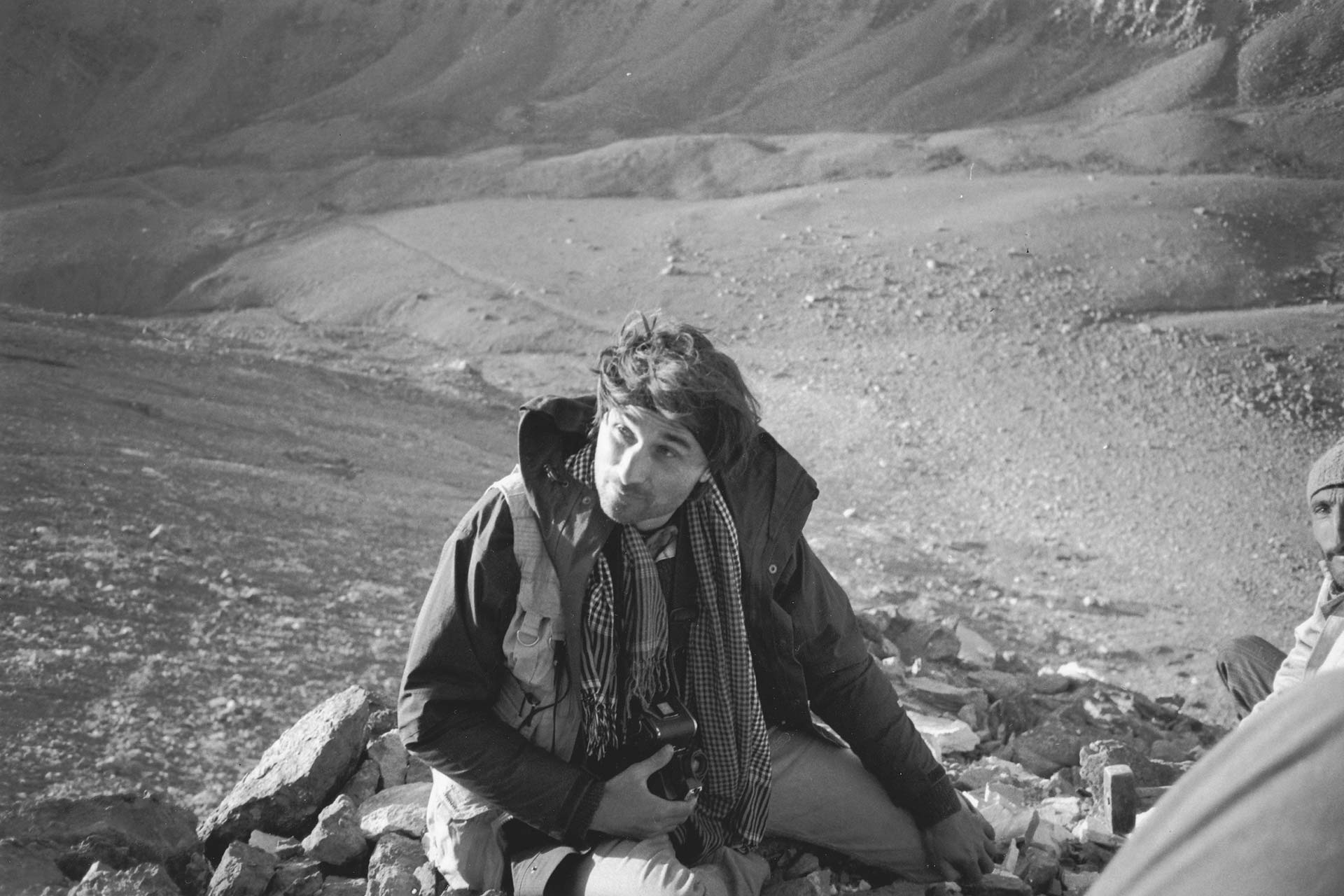

With fourteen photographs by the author as well as typo-/carthography artworks on the endpapers

Selected readings

10th LitCologne International Literature Festival, Köln 2010

14th International Literature Festival, Leukerbad 2009

31st Solothurner Literaturtage, Solothurn 2009

Reviews

»Dies ist ein aussergewöhnliches Buch, und vielleicht hat es noch nie etwas Vergleichbares gegeben – geboren aus der Idee des “verflochtenen Reisens in Raum und Zeit”.«

Frankfurter Alllgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt, 28. Mai 2009

»Folgte Bruce Chatwin den “Songlines”, den Traumpfaden der Aborigines durch den australischen Kontinent, so folgt Daniel Schwartz den von Büchern angelegten Pfaden durch die gewaltige eurasische Landmasse.«

Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürich, 9. April 2009

»Ein erstes Destillat eines sich abzeichnenden Lebenswerks.«

Neue Luzerner Zeitung, Luzern, 23. Februar 2009

»Ausgeprägter Sinn für brennende Themen, bevor sie einer grossen Öffentlichkeit ins Bewusstsein gelangen.«

Schweizer Buchhandel, Zürich, 10. November 2008

»Der Fotograf gehört zur seltenen Spezies seiner Profession, die ebenso des Bildes wie des Wortes mächtig sind. Dem Schreiben kommt das Fotografenauge zugute.«

NZZ am Sonntag, Zürich, 26. Oktober 2008

Books

- 2019–2023Tracings. Photography and Thought

- 2009–2016While the Fires Burn. A Glacier Odyssey

- 1991/95–2007Travelling through the Eye of History

- 1987–2007Schnee in Samarkand.

Ein Reisebericht aus dreitausend Jahren - 1991–1995Delta. The Perils, Profits and Politics of Water in South and Southeast Asia

- 1989How Much Land

- 1987–1988 (1990, 1993, 2000)The Great Wall of China

- 1977–1985Metamorphoses. Greek Photographs