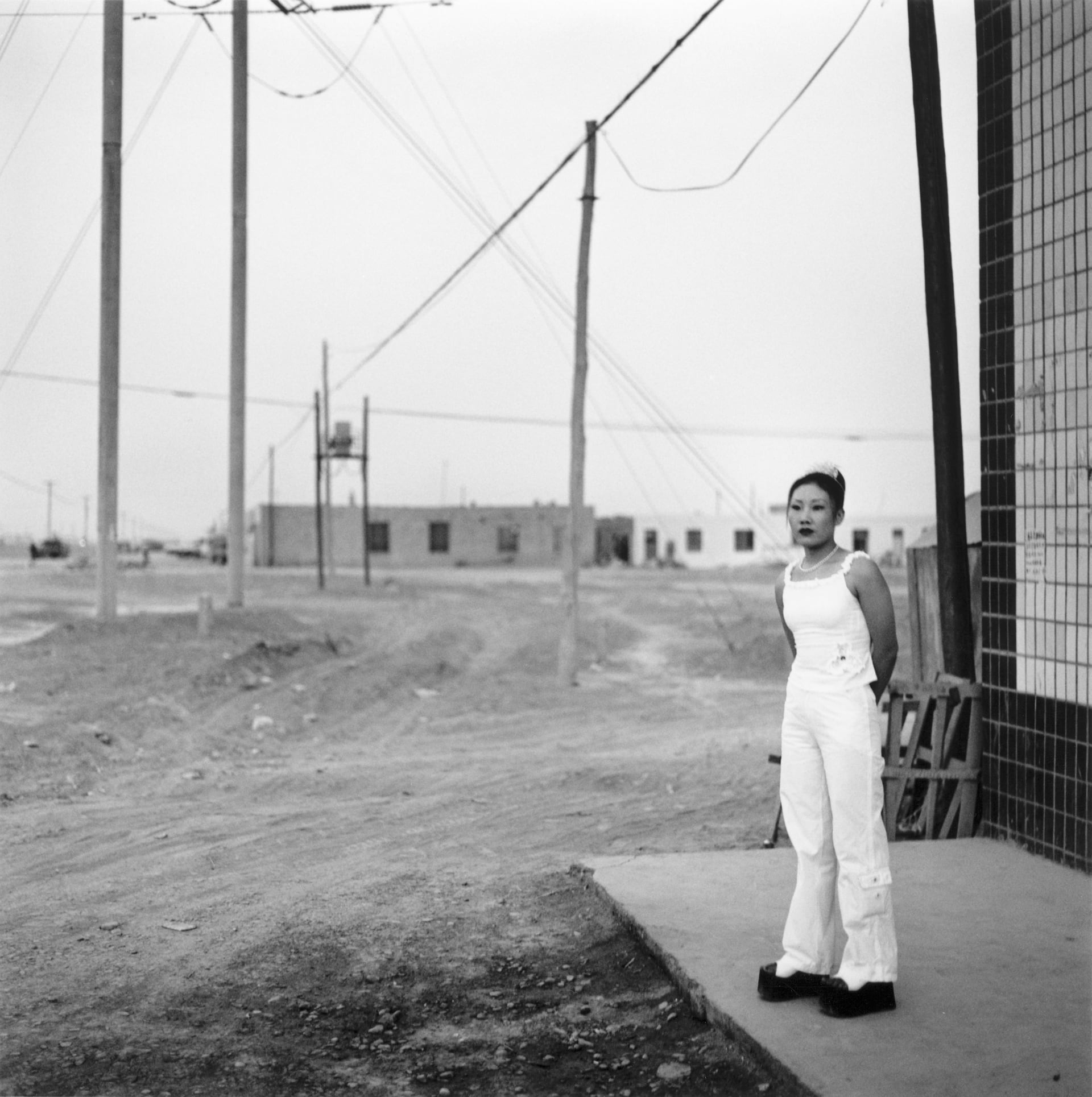

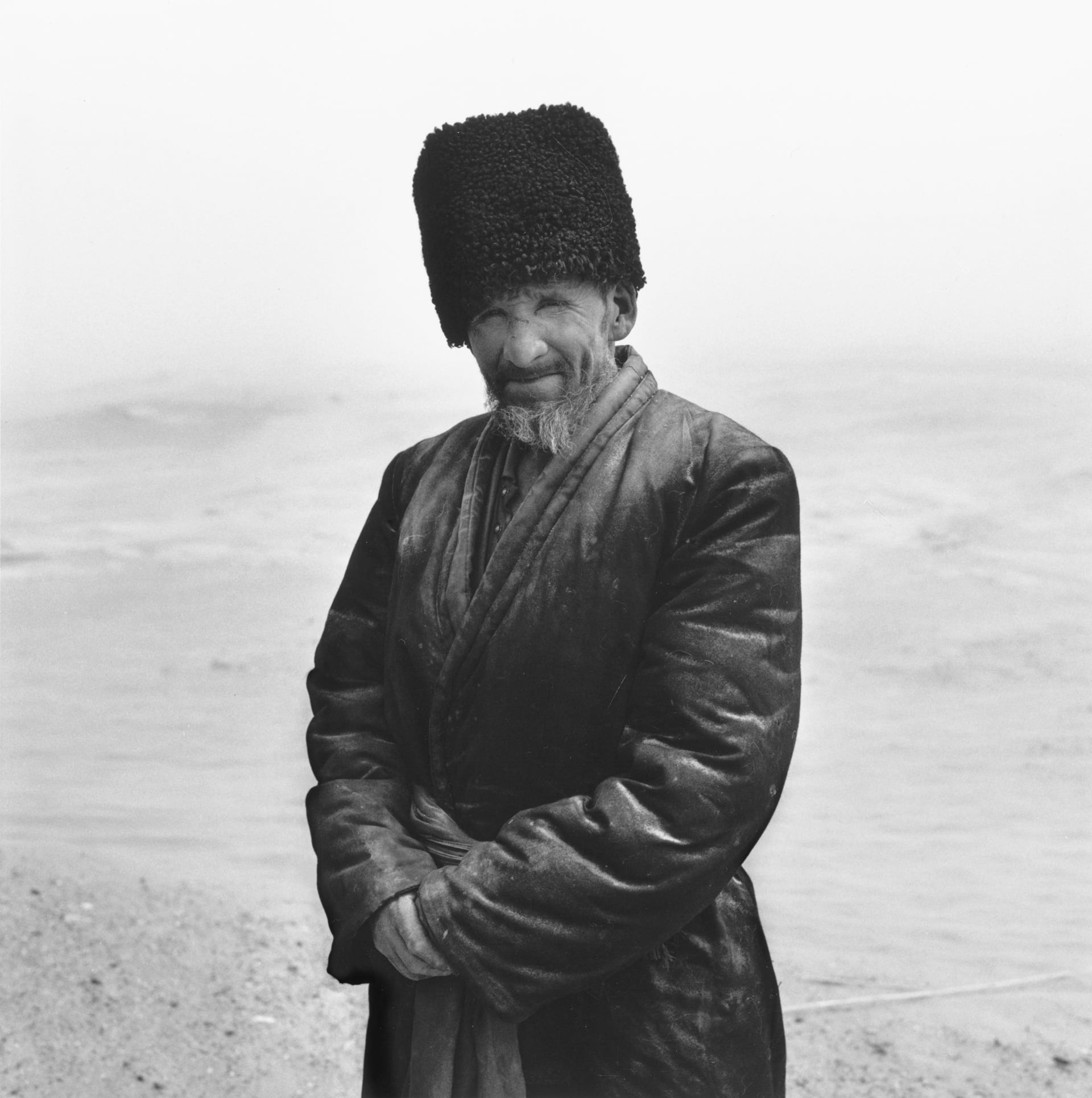

2001

China—The Transformation of Xinjiang

The two stories The Transformation of Xinjiang (2001) and Farewell to Kashgar (2004) about China’s Far West – more precisely about the mineral-rich Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and Kashgar, the fabled Silk Road oasis town and hotspot of the 19th century’s Great Game – were photographed despite the travel restrictions put in place for fear of insurrection when the purge of all but the mildest expressions of the Islamic faith and any yearning at all for an independent Uighur homeland had just begun.

The signs of the “Great Western Development Strategy” (a.k.a. “Open-Up-The-West Program”) launched in 2000 were already apparent, and it was clear that Beijing’s plans to develop the western provinces were about more than just economics and preventing the quarter of the country’s population that inhabits this vast border region from falling even further behind the prosperous coastal region in the east. For Xinjiang, the largest of the provinces around and beyond the bend in the Yellow River, the “Great Western Development Strategy” would be nothing less than the prologue to the most sweeping internment drive since the Mao era, in the course of which more than one million people, Uighurs, Turkic-speaking Muslims, and other Muslim minorities would be imprisoned.

Xinjiangs’s population is now subject to a massive, concerted campaign of indoctrination and coerced sociocultural re-engineering – policies labeled by the Foreign Policy Journal and Center for World Indigenous Studies as “cultural genocide” – and to invasive mass surveillance using tracking software that maps relations with family and friends.

At the beginning of the 21st century, what had been a black hole in the vast savage landscape of Central Asia returned to the light: China’s Far West. In the eyes of the Han Chinese a barbarian land, it was subdued only in the 17th century by means of a genocide committed against the Dzungars and colonized only late and with great difficulty.

After 1949, the Communists continued the old tradition of imperial banishment and transformed Xinjiang – the name means “New Territory” – into a penal colony and gulag. The victims are the Uighurs, who are now prisoners in a homeland they have inhabited for two millennia. They regard as theft what the Han regard as property, but already they are a minority in what, in a nod to two short-lived republics in the early 20th century, they prefer to call East Turkestan.

A 1984 law enshrined in the Chinese Constitution calling for the protection of indigenous institutions provided Beijing with the possibility of a different avenue. This system of “ethnic autonomy” was indirectly derived from the pluralist (though not democratic) ideology of the Qing Empire (1644–1911), which brought Mongolia, Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang under Han rule as a “great family under Heaven.” Adapted to the conditions of the Communist PRC, it worked successfully in the 1950s, when Xinjang was designated the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR), and in the 1980s, and remained popular with minority groups even in the absence of real autonomy.

Before the launch of the “Great Western Development Strategy,” the western half of the country had attracted less than 5 percent of all the foreign investment that flowed into China in the two preceding decades. It seems implausible that the 13 billion dollars which are said to have been made available in 2000, as well as the larger sums that followed, should have come from the central coffers alone. Foreign investors and even banks were courted. The Western Development Strategy’s emphasis on hard infrastructure betrayed China’s colonizing instincts. Roads and railways would make it easier for security forces to be dispatched in times of Muslim restiveness, for Han settlers from the east to seek a new home – the census of 2000 shows the Uighur population reduced to 42 percent of the total, whereas in 1949 Han Chinese had accounted for just 6 percent – and for the center to control every inch of the empire.

Lacking a charismatic leader like the Tibetans and as practitioners of a religion that has been somewhat out of favour in post-9/11 America, the Uighurs’ cause remains obscure. The affiliation of some members of the shadowy Turkestan Independence Movement with al-Qaeda and the Taliban has led to the abandonment of their plight in the interests of geopolitics and has given the Chinese a handy excuse to repress its discontented Muslim minority in Xinjiang.

Assimilation into the Han majority culture – by weakening Uighur as a separate identity, according to a 2014 document endorsed by President Xi Jinping – included the razing of old Kashgar’s traditional architecture and the elimination of the Uighur-language educational track from Xinjiang’s schools and universities. Sporadic unrest like that in 2009 is perceived by the government as a sign of insurrection, which it attributes to foreign-inspired Islamic “terrorism,” even though the real causes are not cyber-radicalization, but local and political.

In 2018, a UN human rights panel cited a World Uighur Congress report, according to which more than one million people – Uighurs, Turkic-speaking Muslims, and other Muslim minorities – were being held in counter-extremism centers, raising concerns that China had turned Xinjiang into “a massive internment camp shrouded in secrecy.” The government denied the scale of the detentions, but acknowledged that “religious extremist” Uighurs were undergoing re-education and resettlement. Comparing the practice to that of Washington in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, it invoked the “War on Terror” to justify the repression as well as the human rights violations that have come with it since it was introduced in 2014.

The periodic crackdown on Islam began almost two decades ago. Religious practice among under-eighteens has been banned in Xinjiang since 1990 and regulations bar students from participating in religious activities, attending madrasas, fasting or wearing religious garb, such as Islamic head coverings, which might spark a backlash and heighten opposition to Chinese rule. As most Uighurs have not reaped the benefits of the economic campaign, their alienation from the Han Chinese may well rise. And the newly enriched Uighur businesspeople could be a source of new funding for nationalists. Regardless of whether the fruits of the campaign eventually trickle down to them, the Uighurs resent the “Great Western Development Strategy” and for them, the Han presence has the emotional impact of an occupation. Xinjiang’s 5,500-kilometer-long frontier with eight, mostly Muslim, countries is the least secure part of China’s border.

As China needs strategic oil reserves, pacifying mineral-rich Xinjiang is vital for the central government. Not surprisingly, many of the “Great Western Development Strategy” projects funneled money into the oil sector. But in the early 1990s, when China’s economic growth had began to surge, Xinjiang failed to deliver as expected. In 2000, the world’s sixth-biggest oil producer’s net crude imports were more as twice what they were in 1999, and by 2020 China will depend on imports for over 50 percent of its oil consumption.

The two reportages were commissioned and published by Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürich, and became part of Travelling through the Eye of History.

Assignments

- 2010–2018Afghanistan – Glacier Walks in Times of War

- 2012Burma Revisited

- 2009Swat – Mutilated Faces

- 2007Kazakhstan – Oil Great Game in Central Asia

- 2005Turkmenistan – A Journey under Surveillance

- 2004China – Farewell to Kashgar

- 2001–2010Afghanistan – A Thirty Years War

- 2001China – The Transformation of Xinjiang

- 2001Afghanistan – Drought and Famine

- 2000Kashmir – Paradise Lost

- 2000Ulanbataar – Children’s Underworld

- 2000London – Going Southwark

- 1999Indonesia – East Timor: Times of Agony

- 1998–1999Borneo – Destruction Business

- 1998Afghanistan – Economy of Survival

- 1997Cambodia – Quiet Days in Pailin

- 1996Tajikistan – Forbidden Badakshan

- 1995Iran – Roads to Isfahan

- 1994–the presentAngkor – The Mercy of Ruins

- 1994Bangladesh – Sandwip: An Island disappears into the Sea

- 1993Calcutta – Durga Puja

- 1992–1996Indochina – Legacies of War

- 1992Cambodia – Resurrecting a Country

- 1991–1992Burma – Behind the Bamboo Curtain

- 1990Ahmedabad – Cotton Mills

- 1987China – The Pulse of the Earth

- 1978–1980Greece – Lavrion Silver