2010/2018

Afghanistan – Glacier Walks in Times of War

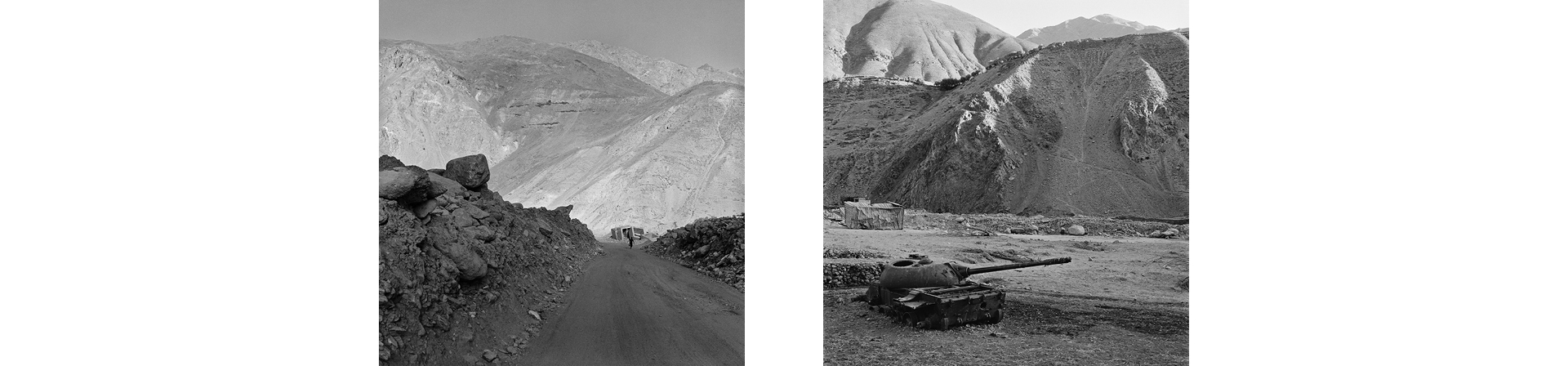

Fighting in Afghanistan increasingly takes place outside the traditional season – a sign that factors driven by climate change might have contributed to the precarious security situation in the drought-prone Hindu Kush, where glaciers are a source of the water needed for critical, late-season crop irrigation, meaning that their retreat and fluctuations are not without implications for the rebuilding effort and, most notably, food security. Hence glaciers have indirectly become a variable of the current course of war. And since war never cares about the needs of the environment, it contributes to its destruction. Over the past twenty years, 50 percent of Afghanistan’s arable land has remained uncultivated and seventy percent of its forests have disappeared

During the past eighteen years of fruitless peace-enforcing and nation-building by the international community – an embroilment causing 32,000 documented civilian casualties and another 60,000 wounded (by mid-2019) – the health of the glaciers in the Hindu Kush was not considered an issue. Today, as Washington is in the process of setting the terms of a negotiated capitulation and the Taliban insurgency is morphing into a government in waiting, filling the vacuum which U.S. and Afghan forces left when they pulled out from the rural areas they had been fighting and dying for since 2001 to protect the urban centers, the country is facing an imminent water crisis. The impending worst-case scenario of ongoing glacier melt therefore implies displacement and migration to densely populated, intensely used agricultural areas and conflicts over water as an already scarce commodity – all intertwined with the fallout of a forty years’ war.

The photograph of armed Afghans sitting on a glacier table is redolent of 19th tourism in the Alps; here, it is above all a metaphor.

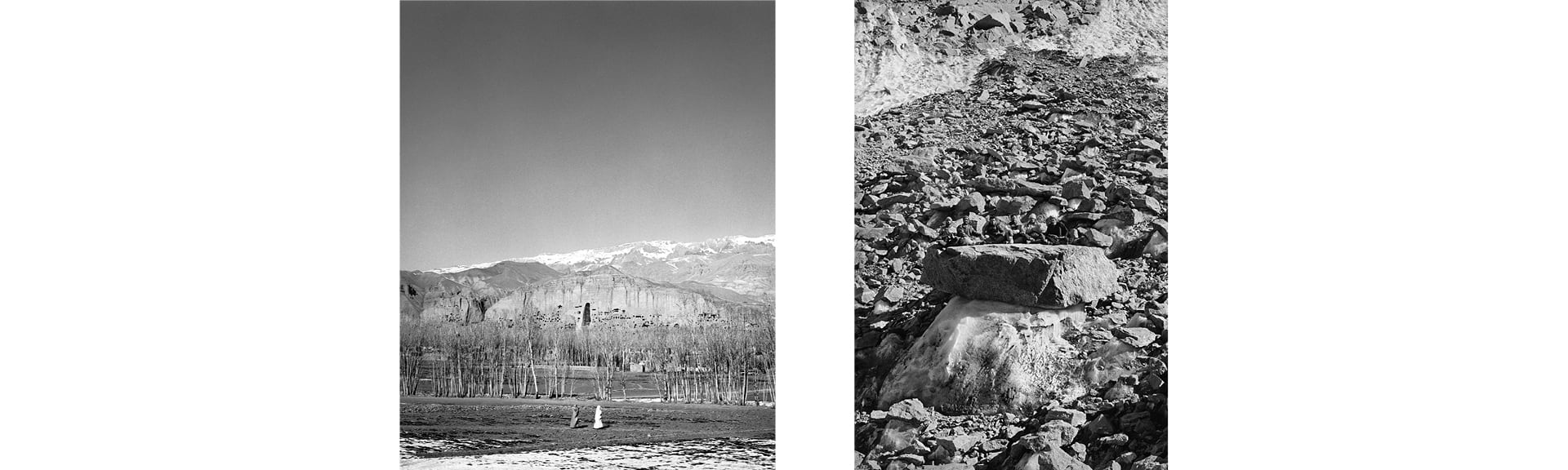

In January 2010, the Fuladi glaciers in the Kuh-e-Baba range in Central Afghanistan – which in the late Pleistocene produced sets of terminal moraines as low as 2,600 M.A.S.L. above Bamian – were out of reach due to the security situation. In September 2018, more precisely during the eight days from 7 to 14 September – almost forty years after Moscow’s 40th Army crossed the Amu Darya (on 27 December 1979) – 400 members of the Afghan military and security forces (foreign-trained, -advised and -assisted) were killed in Taliban attacks. That translates into 50 per day or twice the number (26) that were killed during the bloodiest days of 1984 towards the end of Phase Two of the Soviet-Afghan War.

During that week I visited the relics of the glaciers at the foot of the stunning pyramid of Mir Samir (5,809 M.A.S.L.), hidden away on the border between Panjshir and Nuristan. The mountain is the real protagonist of Eric Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush (1958). My own walk took place sixty years after the publication of the Englishman’s seminal travelogue and just a month after a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) destroyed an entire Panjshir village. Such disasters are a consequence of global warming and related glacial melt, and places with no history of glacier monitoring or surveillance are especially vulnerable.

Not much is known about the glaciers in Afghanistan. The field-based efforts were interrupted by the Soviet invasion of 1979. Detailed glacier maps do not exist, but even as late as 1958–59, the glaciers can be seen reasonably clearly on a scale of 1:100.000, despite problems of compatibility between American and Russian maps. In 2010, the Hindu Kush glaciers reappeared in a survey for untapped Afghan mineral resources including copper, gold and lithium conducted for the U.S. Geological Survey. The ASTAR high spatial resolution data stereo images revealed evidence that the glaciers had completely disappeared in most cirques below about 4,000 M.A.S.L. The retreat of the past three decades is continuing and has disconnected tributary glaciers from the main trunks. Before, the analyses of early low-resolution satellite images had confounded clouds and highly reflective rocks with snow and ice – just as hasty analysis of video footage more recently collected by drones in the fog of war confounded fighters with civilians.

In 1989, the war begun in 1979 as an impetuous Soviet invasion morphed from a mechanized Cold War proxy into a protracted civil war fought by ethnic and political Mujaheddin factions and fuelled by regional powers, leading to the Taliban Surge of 1994. By avoiding taking sides in the internecine fighting and striving to be seen as a neutral force, the Islamic emirate that the Taliban built brought Afghanistan back into the West’s field of vision – though only after becoming host to Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda.

The attacks of 9/11 provoked the brief anti-Taliban War, a campaign that the United States in 2003 relegated to a supportive war of the occupation of Iraq (sparking the arrival in Afghanistan of IED technology and suicide-bomber tactics experts), but conducted within the wider framework of a “War on Terror” (illustrating Washington’s fears about rogue states, state-sponsored terrorism and the transfer of WMDs) – distractions that after 2002 obscured the Taliban’s regrouping and bedeviled the counterinsurgency efforts for many years to come.

The old-new foe opposed both the U.S./Allied intervention force under the NATO umbrella and the two Kabul governments which the Western alliance installed to serve its needs and fulfill its ambitions – tasks that the two puppets could not, or would not, deliver.

Planned for inclusion in While the Fires Burn. A Glacier Odyssey the visit of the Mir Samir glaciers became only possible after publication of the book. The reportage was subsequently commissioned and published by Das Magazin, Zürich.

Exhibition

While the Fires Burn. A Glacier Odyssey

Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, 2018/2019

Group exhibitions

Afghanistan. The Endless War

www.warmfoundation.org

The History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegowina, Sarajevo 2019

Ancienne école primaire Alain Chartier, Bayeux 2919

Assignments

- 2010–2018Afghanistan – Glacier Walks in Times of War

- 2012Burma Revisited

- 2009Swat – Mutilated Faces

- 2007Kazakhstan – Oil Great Game in Central Asia

- 2005Turkmenistan – A Journey under Surveillance

- 2004China – Farewell to Kashgar

- 2001–2010Afghanistan – A Thirty Years War

- 2001China – The Transformation of Xinjiang

- 2001Afghanistan – Drought and Famine

- 2000Kashmir – Paradise Lost

- 2000Ulanbataar – Children’s Underworld

- 2000London – Going Southwark

- 1999Indonesia – East Timor: Times of Agony

- 1998–1999Borneo – Destruction Business

- 1998Afghanistan – Economy of Survival

- 1997Cambodia – Quiet Days in Pailin

- 1996Tajikistan – Forbidden Badakshan

- 1995Iran – Roads to Isfahan

- 1994–the presentAngkor – The Mercy of Ruins

- 1994Bangladesh – Sandwip: An Island disappears into the Sea

- 1993Calcutta – Durga Puja

- 1992–1996Indochina – Legacies of War

- 1992Cambodia – Resurrecting a Country

- 1991–1992Burma – Behind the Bamboo Curtain

- 1990Ahmedabad – Cotton Mills

- 1987China – The Pulse of the Earth

- 1978–1980Greece – Lavrion Silver